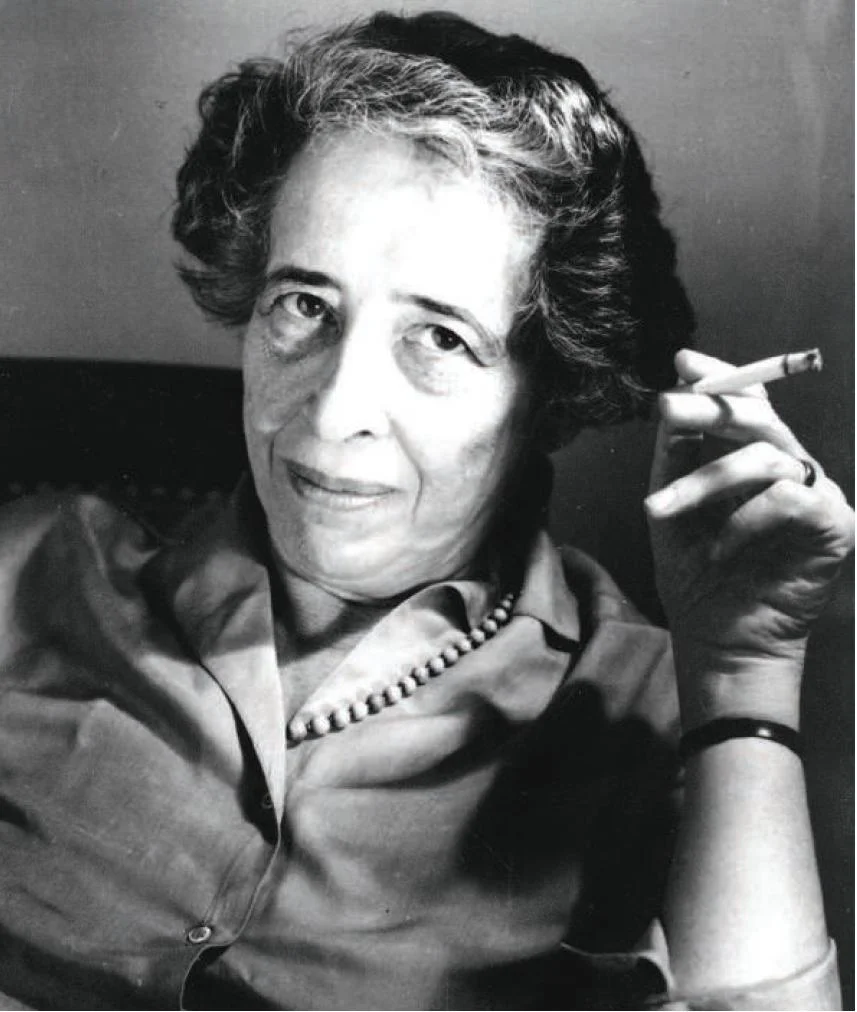

Hannah Arendt and the Lost Art of Thinking

Catch up on podcast episodes! Bitchstory

Join Patreon and get weekly Bitchscopes & more!

Hannah Arendt did not believe that evil always looks like a monster…Sometimes, she said, it looks like a man doing his job.

“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

Arendt was a German-Jewish political theorist who fled the Nazis, landed in the United States, and spent her life trying to understand how ordinary people become participants in extraordinary harm. Her most famous phrase — “the banality of evil” — came from watching Adolf Eichmann, a bureaucrat who helped organize the Holocaust, insist he was simply following orders. He wasn’t a sadist. He wasn’t foaming at the mouth. He was dull. Career-minded. Proud of his efficiency. Empty of thought.

That emptiness is what terrified her.

Arendt argued that the real danger isn’t just hatred or cruelty. It’s the suspension of thinking — the decision to stop examining what we’re doing, repeating, supporting, or excusing. When people trade judgment for obedience, belonging, or comfort, systems of harm don’t need villains. They only need compliance.

Sound familiar?

She also believed that thinking is not the same as intelligence or education. Thinking, to Arendt, was a moral activity. A habit of stopping. Questioning. Refusing slogans. Asking: What does this mean? Who does this harm? What kind of person does this make me?

In the present-day U.S., we are drowning in opinions and starving for thought.

We reward certainty over curiosity. Loyalty over conscience. Volume over reflection. We sort ourselves into teams and outsource our moral labor to hashtags, party lines, and cable news chyrons. We call it being informed. Arendt would call it dangerous.

She warned that totalitarianism doesn’t begin with soldiers. It begins with language that flattens people into categories, narratives that excuse cruelty as necessity, and citizens who stop bothering to think because thinking is inconvenient, lonely, or socially expensive

“The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction no longer exists.”

Arendt was not comforting. She didn’t offer easy heroes or clean absolution. She insisted that responsibility survives even inside broken systems. That no one gets to be “just a cog.” That refusing to think is itself a choice.

Which is exactly why we need her now.

Not as a statue. Not as a quote on a tote bag. But as a thorn.

A reminder that democracy is not protected by vibes or flags or algorithms, but by ordinary people doing the unglamorous work of thinking carefully, judging independently, and resisting the seductive relief of letting someone else decide what is true, who is human, and what is acceptable.

Hannah Arendt didn’t believe thinking would make us pure.

She believed it might keep us from becoming monsters in sensible shoes.